Learning How to Suffer

It helps if others walk alongside us.

Photo: David Redfern/Redferns

I recently saw the Angelina Community Theatre production of the one-act play, Wit, by Margaret Edson. It was excellent. This play, which won the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1999, deals with a brilliant English professor’s journey with advanced ovarian cancer. She approached her disease as an academician – distant, thoughtful, precise. Even so, the ravages of chemotherapy (“always full dose”) and advancing disease ultimately killed her. Her doctors were the epitome of emotionless detachment. As a stoic, it was “her mind and the sonnets of John Donne [that served to] protect her from the relentless ferocity of modern medicine.” However, I was also struck by the compassion of a lone nurse who saw her as a person – an individual – who was suffering.

As a cancer and hospice physician – one who has spent a career striving to cure cancer and comfort those who are suffering – Wit reminds me of the very personal nature of suffering and the individualized approach needed to cope.

Suffering, by definition, is bad. Evil, some would say. Rabbi Harold Kushner, author of When Bad Things Happen to Good People, believed the presence of suffering was evidence of evil, and that God is present with people during their suffering but not fully able to prevent it. Christian Reformed theologian R. C. Sproul wrote an entire book on suffering called Surprised by Suffering. Dr. Sproul believed all suffering has a purpose – the salvation of our souls – and that if we view our suffering as meaningless, we are tempted to despair. I do not believe suffering always has a meaning or a purpose. Sometimes, as the bumper sticker acknowledges, sh*t happens.

Sometimes, sh*t happens.

A book that deepened my knowledge of both medicine and theology was written by Paul Brand and Philip Yancey back in 1980 - Fearfully and Wonderfully Made. Dr. Brand was a renowned hand surgeon, researcher, and expert on pain and leprosy. They explain that pain protects us, but there are times when pain no longer serves a purpose. Chronic cancer pain, for example, is only distressing and of no biological use. C. S. Lewis wrote, “No one can say ‘He jests at scars who never felt a wound’, for I have never for one moment been in a state of mind to which even the imagination of serious pain was less than intolerable.” To which I say amen.

Dane Cicely Saunders, founder of the modern hospice movement, helped us understand that pain and suffering are not just physical. She coined the phrase “total pain” to include physical, psychological/emotional, social, and spiritual aspects of pain and suffering. Efforts to relieve suffering must therefore extend beyond the physical.

Efforts to relieve suffering must extend beyond the physical.

Some suffering is reasonable in the pursuit of longer-term goals, such as curing disease or prolonging life. But other suffering is egregious harm and often avoidable: continued treatment when such treatment is futile; end-of-life resuscitation of a person beyond recovery; financial bankruptcy from healthcare expenses.

Philip Yancey, writing in Where is God When it Hurts, notes that there are two major attitudes which can drastically affect our ability to withstand pain and suffering: fear and helplessness. Yancey writes, “A suffering person desperately needs some resources which any of us can give: love, hope, a sense of presence.” I often hear my patients express fear of being a burden to others. I remind them that their loved ones want to be of service to them and they should not deny them the opportunity – the gift – of ministering to them.

In The Wounded Healer, Henri Nouwen writes about a patient named Mr. Harrison (only 48, needing an operation to save his legs from amputation due to poor circulation) who was described as having not only a fear of death, but a fear of life. This “psychic paralysis” was a source of intense suffering. Nouwen discerned that Mr. Harrison’s condition was a desperate cry for a human response – a personal response – from others. That response, as Yancey noted, starts with presence. No one wants to live alone, die alone, and certainly not suffer alone. Yet finding the right person to travel with – who will honestly not tire of suffering with you – is not easy. (That is the very definition of the Holy Spirit – the paraklete, the Comforter – who will never leave us.) For those ministering to others: If you are going to start the journey, be prepared to finish it.

Those who are suffering don’t need preaching; they need presence.

For those of us being a presence for others who are suffering, we must resist the temptation to think that our own suffering, if any, is the same as what the sufferer is experiencing. Everyone suffers, grieves, and hurts in their own way. Though we may have experiences that could shed some light on the path of others, their journey is not ours, and they must find their own path through suffering.

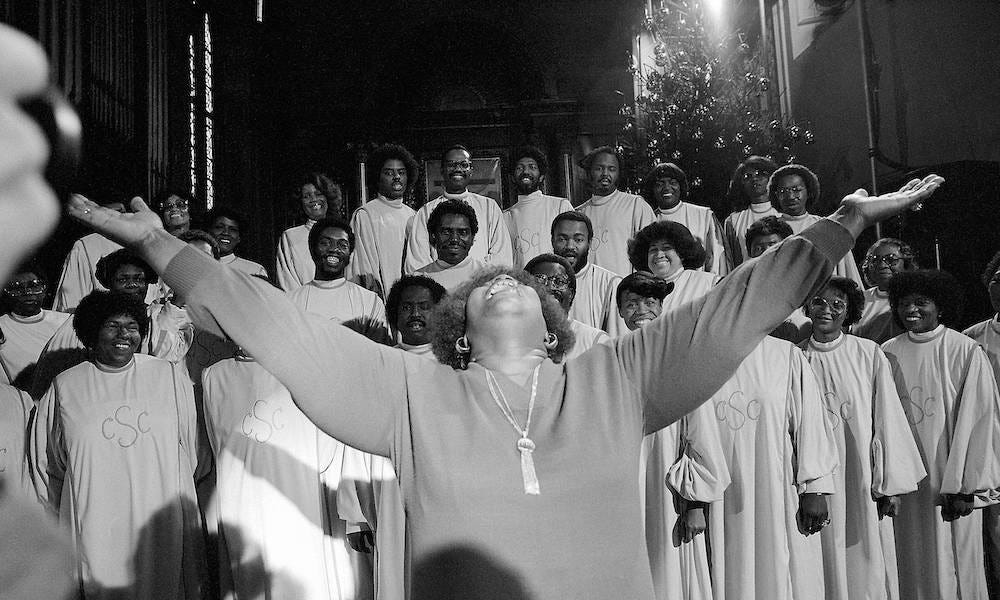

There is something profound in listening to others share their suffering through music, where emotions are real and raw. Adam Gussow, author and blues harmonica player, wrote that blues songs “traffic in suffering.” Regarding what he calls the blues ethos, pain is acknowledged to help evade suffering. “See it, say it, sing it, share it. Get it out, by all means. Don’t deny the pain, or hide from it. But don’t wallow in it, either.” Gospel music similarly gives voice to common suffering as well as hope to overcome, with that hope often expressed in eternal terms.

A note of caution: Those of the Christian faith especially must resist the urge to “preach” to the suffering. As God chastised Job’s accusers, we assume with great risk to our own souls that we know the reasons for others’ suffering, much less the solutions. Some suffering has no meaning, no purpose. It must simply be endured. Ultimately, no one can teach us how to suffer. But it helps if others walk alongside us, demonstrating God’s love. Are you loving your neighbor?

Thanks Sid. As I age, what you wrote repeatedly resonates with me, “ No one wants to live alone, die alone, and certainly not suffer alone.” I worry about growing old alone, wishing fruitlessly for a larger family - by blood or by love and friendship.

Thank you, Dr. Sid. This has essentially portrayed the nature of our tiny country church we are part of…we chose it because it is close to our home out here in the woods. But we quickly realized this is a community of like- minded, like-faithed and same in age as we are. We hear solid word from scripture come to life in our sprits; we care deeply for each other; we talk things out…we grieve together…rejoice together…know the good the bad and the ugly going on …and during the week we share by text, phone calls and visits…just to make sure we are all still vertical. THAT is a blessing and we do not stop with just our “own”…there is a huge neighborhood out here in these towering pines. What a treasure when we “find” another to make contact with.